A Short History of the Fulbright Program: “An Avenue of Hope”

The Fulbright Program is one of the largest and best known fellowship programs in the world. It permits American students, teachers, scholars, professionals, artists and scientists to compete for scholarships or grants to study, conduct research, teach, or showcase their talents abroad; and citizens of other countries (such as the Netherlands) may qualify to do the same in the United States of America.

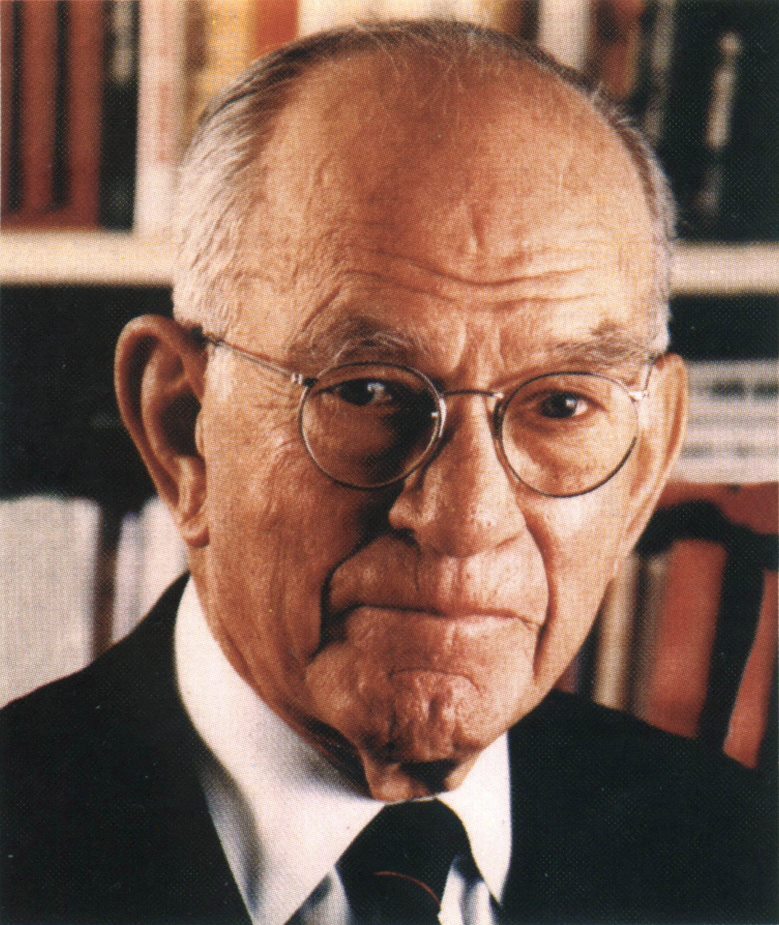

According to Senator J. William Fulbright, the founder of the program, the aim of the program is “to erode the culturally rooted mistrust that sets nations against one another. Its essential aim is to encourage people in all countries, and especially their political leaders, to stop denying others the right to their own view of reality and to develop a new manner of thinking about how to avoid war rather than to wage it. The exchange program is not a panacea but an avenue of hope – possibly our best hope and conceivably our only hope – for the survival and further progress of humanity” Having just seen the Second World War end with the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Fulbright was looking for ways to foster international understanding. He believed that the only way to permanently stop wars was to make people understand each other and other cultures.

The idea came from Fulbright’s own experience as an exchange student. Jay William Fulbright grew up in a small town in the north of Arkansas. Before he got a Rhodes scholarship to go to England, he had never seen the ocean or even a big American city. The Rhodes scholarship however enabled him to visit another country and culture. He described the experience as a “culture shock.” The attitude of the English students was much more studious and this resulted in Fulbright putting more effort into his studies. Fulbright came back to the United States as a more motivated man with more knowledge of the world.

Even though the benefits of an exchange program were clear to Fulbright, he knew that the rest of the Senate would not feel the need for it. Thus, as a “soft sell,” he decided to combine his proposal with another issue the Senate was dealing with after the war. During the Second World War, the American armed forces had left supplies in the countries they had been operating in. Most countries in Western Europe and several others in the rest of the world had vast supplies of food, blankets, trucks and other assets that the Americans had left behind. The idea was to sell these assets to the countries they were in, because bringing them back to the United States was too expensive. The problem with this idea was that most countries would have to pay in nonconvertible credits and IOUs, since they were unable pay in dollars. Fulbright pointed out that the US had been forced to nullify most of the debts owed to the US after the First World War, because the indebted countries had defaulted. His program would ensure that this time around, the US would get something out of the credits, by using them to fund educational exchange. That way, the program would not have to make use of American tax dollars, and would at the same time solve the issue with the supplies. By presenting his program in this way, Fulbright managed to get his bill approved in 1946.

The Fulbright program got started in 1948 when 65 Americans went overseas, and 35 students and one professor came to the US. Two decades later, exchange programs had been set up with 110 countries and geographical areas. By 1966, twelve million schoolchildren had been taught by exchange teachers, and 82.585 individuals had received Fulbright scholarships. The program flourished during the Cold War era and several scholars have made the argument that the Fulbright program played an important part in the “cultural” Cold War. At the same time that American citizens were sharing the American culture with their host countries, the Soviet Union had its own exchange programs. Students from their satellite states were encouraged to visit the Russian universities and learn about Marxism and Stalinism. The Fulbright program was supposed to offset this propaganda by converting the exchange students to the American way of life.

Nowadays, the Cold War is over, but the Fulbright program is still going strong. According to the website of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, the Fulbright Program is active in more than 160 countries. Among the Fulbright alumni, 37 have served as a head of state, 60 have been awarded with a Nobel Prize, 86 have been awarded with a Pulitzer Prize, and 75 have been awarded McArthur Fellowships.

The Roosevelt Institute for American Studies (RIAS) is responsible for the archives of the Dutch section of the Fulbright Program. The Netherlands has been part of the Fulbright Program since nearly the beginning. In 1949, the bilateral USEF (United States Educational Foundation) was established in Amsterdam as the Dutch counterpart to the American organization. Since then it has changed its name twice. USEF became NACEE (Netherlands America Committee for Educational Exchange) in 1972. NACEE in turn became the Fulbright Center in 2004. The collection at the RIAS offers documentation from 1949, the founding year of the Dutch-American exchange program, up to the present day. Candidates’ files and general program material are present starting from 1985. The collection came to the RIAS in Middelburg in 2007 when the Fulbright Center in Amsterdam ran out of space and looked for a safe depository for its historical archives. The RIAS was a logical place for these holdings, since this research institute is a key player in Dutch-American scholarly relations and has access to professional archival storage space.

This piece was written using the follows books:

– J. William Fulbright, The price of empire (New York 1989) 215-18.

– Anne Wil Petterson, Studie richting Amerika : alles wat je moet weten over studeren in de Verenigde Staten (Amsterdam 2006) 51-2.

– Randall Bennett Woods, J. William Fulbright, Vietnam, and the search for a Cold War foreign policy (New York 1998) 9.