Isolationism vs Internationalism: The Debate about US Neutrality within FDR’s Administration

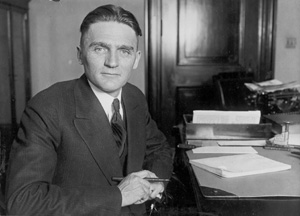

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration is often remembered for its ‘New Deal’ that got the United States out of the Great Depression, and for its involvement in the Second World War. However, another interesting chapter of FDR’s long presidency is its attitude toward neutrality and intervention during the interwar years. Between 1935 and 1939, the neutrality acts and several amendments to them were implemented in order to keep the United States out of any international conflict. Within FDR’s own administration, however, there were many outspoken critics of neutrality. Cordell Hull, FDR’s Secretary of State thought that the neutrality legislation was confining the US to a passive role in world affairs. Other US policymakers, including republican senator Gerald Nye and democratic senator Bennet Clark were supportive of isolationist stances.

Through the study of several documents held by the Roosevelt Institute for American Studies it is possible to reconstruct this discussion between non-intervention and intervention and contextualize it both politically and historically.

The First Neutrality Acts stemmed from the work of the so-called Nye Committee, the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, which was named after its chairman Gerald Nye. The Nye Committee was responsible for investigating financial motives of banks and other financial institutions for the participation of the US in the First World War. The ultimate aim of the committee was to prove that the United States had been pushed into the War by bankers and munitions makers. In order to prevent this from happening again, the Nye Committee started to push for neutrality by legislation. This push ultimately resulted in the First Neutrality Act, which was passed by Congress on August, 31, 1935. The First Neutrality Act prohibited trade of goods vital to the war effort to all belligerent nations.

Nye argued that wars in the modern era were fought mostly for economic causes, instead of political ones. Nye chiefly based this on the loans the British and French governments had with American banks during the First World War. To further strengthen this argument, Nye quoted President Wilson. ‘’Why, my fellow citizens, is there any man here or any woman, let me say is there any child here, who does not know that the seed of war in the modern world is industrial and commercial rivalry? …. This war in its inception was a commercial and industrial war. It was not a political war.’’ Nye therefore, stated that it was imperative for the United States not to become economically entangled in any conflict. The way to ensure economic disentanglement from conflicts was to ban the trade of goods that were deemed vital to the war effort of all belligerent nations involved in a conflict. Nye argued that this was precisely what the neutrality acts entailed to achieve. Neutrality by legislation was therefore necessary to prevent American banks or ammunition manufacturers from dragging the United States into a new war, a war that would again be fought based on economic motives.

The recommendation of the Nye Committee reflected an overall support for pro-isolationist stances within the public opinion. This explains why, even if he disagreed on a personal level with the recommendation of the Committee and the provisions of the neutrality act, Cordell Hull advised the president to endorse the legislation anyhow: ‘’In spite of my very strong and, I believe, well founded objection to this joint resolution, I do not feel that I can properly, in all the circumstances, recommend that you withhold your approval.’’

Hull believed that the duty of the United States was, firstly, to attempt to stay out of conflict, and secondly, to promote the interests of international peace as much as possible. This second duty, promotion of global peace, could not, according to Hull, be exercised to its fullest extent if the country committed itself to neutrality. Moreover, the First Neutrality Acts equally imposed sanctions on all belligerent parties, whether they be aggressor or defendant. This was the crux of the problem for Hull, since he believed that it was the duty of a neutral nation to determine who the party in the right was, and to not withhold aid to this party. Therefore, he proposed that the president should be given authority to determine who the aggressor of the conflict was, and be able to place embargoes on the aggressor’s side alone. This would, according to Hull, ensure global peace due to the fact that the aggressor alone would be hampered in conflicts, while the defendant would still receive goods vital to the war effort from the United States. True neutrality would in this case not be achieved, but as Hull stated in his memoirs, true neutrality was not his goal. His aim was to foster cooperation among all peaceful nations and isolate the aggressive ones. Additionally, by stating that the United States would solely target the aggressor of the conflict, to Hull would have represented a good deterrent as nations would think twice about instigating a conflict. In conclusion, Hull argued, this stance would make the world more peaceful than in the case were the United States would isolate itself from the world theatre and deny any help to all belligerent nations.

Both Nye and Hull shared a desire for peace but landed on a completely different course of action to ensure it. While Hull advocated for an active international role of the United States in order to keep the world at peace, Nye wanted to retreat and the US to remain aloof in future conflicts. The progressive involvement of the US in WWII and the renegotiation of the neutrality legislation through the cash and carry and the lend-lease policies, thus, were the results of long and harsh negotiations not only with Congress but also among the members of FDR’s administration. The RIAS sources help to uncover this debate and shed light on the complexity of the American foreign policymaking.

This piece was written using the following book available at the RIAS:

– Cordell Hull, ‘’The Memoirs of Cordell Hull: Volume 1.’’ The Macmillan Company: New York, 1948. Pp 398-403.

And the following microfilm reel available at the RIAS:

– The Papers of Cordell Hull Conts 82-83, 413 DM 16, 160, Reel 47 of 118.